Lu Yu’s book, the Ch’a Ching, or The Classic of Tea, was hugely popular in his homeland of China, but its influence was particularly potently felt in Japan, where it led to the foundation of the Tea Ceremony. This ritual, known as Ch’a No Yu, has elevated the preparation and drinking of tea to an art form which continues to flourish to this day.

Lu Yu’s book, the Ch’a Ching, or The Classic of Tea, was hugely popular in his homeland of China, but its influence was particularly potently felt in Japan, where it led to the foundation of the Tea Ceremony. This ritual, known as Ch’a No Yu, has elevated the preparation and drinking of tea to an art form which continues to flourish to this day.

Tea was almost certainly introduced to Japan by Buddhist monks, and certainly originally, tea drinking remained the exclusive preserve of the the Buddhist priesthood. But in 1119, a Zen Buddhist monk by the name of Eisai brought new seeds back from China to Japan, along with knowledge of Lu Yu’s book, and so laid the foundations for the Japanese Tea Ceremony.

This ritual is based on Zen Buddhist monks’ belief that the right preparation and consumption of tea is an aid and stimulant for deeper meditation. The ceremony caught on and gained in popularity, and Eisai went on to pen the first book on tea in Japan, the Kitcha Yojoki or Book of Tea Sanitation.

As the popularity of the beverage gained momentum, there was a commensurate interest in the Tea Ceremony, which soon became regarded as the most unique and quintessential way of expressing a degree of social sophistication, in the most exquisite of settings. And much more than that, it expressed the Zen Buddhist belief that the small, everyday chore is as important as the most crucial universal spiritual principle. That the mindful ritual of making tea, celebrated the greatness that can be found in the humblest of everyday tasks, and that the grace and delicacy with which the tea ceremony is performed is an outward display of the importance of an inner peace and harmoniousness.

Don’t get me wrong! This beautiful ceremony took a while to gain footing. Originally, the tea ceremonies were somewhat riotous affairs, with copious amounts of alcohol drunk alongside the tea! Gradually, however, they got more and more refined, partly due to three Tea Masters. The last of these, Sen No Rikyu (1522-1591), who lived in Kyoto, is responsible for introducing all the Zen elements to the Tea Ceremony. It is the form he developed, chado, the way of tea, that is practiced in the Japanese Tea Ceremony to this day.

Sen No Rikyu became personal Tea Master to the powerful politician, Hideyoshi, and his chief aide. The relationship between the two men was strong until other courtiers, jealous of his influence, turned Hideyoshi against him, and he was forced to commit seppuku, ritual suicide.

Despite this horrible death, Rikyu’s sons and grandsons continued to practice chado and today, the Urasenke Tea tradition (the largest of the different Ways of Tea) is headed by Grandmaster Zabosai Sen Shoshitsu XVI, the sixteenth generation of direct descendants of Rikyu to hold the post.

The tea ceremony itself takes place in a Sukiyu, a simple wooden building with a sloping roof. There is an anteroom, a midsuya, a small chamber where the utensils are washed, laid out and prepared, a portico or machiai where guests wait to be summoned into the tea room, and a path through the garden that surrounds the tea room, the roji, that connects the world outside with the haven of calm that is the tea room.

In a sense, the roji represents the journey we must make to reach this inner point of peaceful tranquility. So the walk through the garden is the start of the meditation, representing as it does a step away from the clamour of the outside world, and should be done in silence and in order of precedence. Samurai warriors were obliged to leave their swords on a rack for the purpose. Each guest bent low to get through the door to the tea room, a feature designed to imbue each guest with a sense of humility.

The Chanoyu ceremony takes place in a wooden or bamboo teahouse called a Chashitsu. There is usually room for four people. The garden around the teahouse is very simple with lots of green plants rather than flowers, a small rock garden, and a stream. A path winds its way through the garden leading to the teahouse. If you are invited to a Chanoyu tea ceremony there are certain rules you need to follow.

First you must wait at the entrance to the garden until you are calm and ready to step into it. The Teishu or tea master welcomes you when you are in the garden. He or she brings fresh water for you to drink and to wash your hands. Now you follow the Teishu along the path to the teahouse. Once iinside the teahouse, the Teishu makes the tea using powdered green tea called ‘matcha’. The tea is mixed with boiled water using a bamboo whisk and served in small bowls.

Guests sit on the floor of the teahouse around a low table. When the Teishu gives a guest a bowl of tea, they should bow, take the bowl with the left hand, and then hold it with the right hand. They then place the bowl in front of them and turn it to the right so that they don’t drink from the side that was facing them. Usually the Teishu gives each guest a sweet cake or a mochi to eat as well because the tea is bitter.

When the guest has finished their tea, they should turn the bowl to the left and place it on the table in front of them – having drunk it all! They then turn the bowl to show the Teishu respect: this means that the edge of the cup he gave the guest was the best, but the guest is not the Teishu’s equal, so not good enough to drink from that side. Sometimes the guests share one bowl that they pass around.

When the guest has finished their tea, they should turn the bowl to the left and place it on the table in front of them – having drunk it all! They then turn the bowl to show the Teishu respect: this means that the edge of the cup he gave the guest was the best, but the guest is not the Teishu’s equal, so not good enough to drink from that side. Sometimes the guests share one bowl that they pass around.

The Sencha ceremony, is more relaxed than the Chanoyu ceremony. The rules for serving the tea are traditional but the occasion is more easy-going for the tea drinkers. Most people in Japan don’t have their own teahouse but they often belong to a ‘tea club’ where they go every week to take part in the tea ceremony.

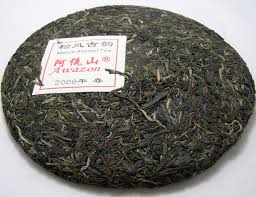

The art of drinking and serving tea in China is much more relaxed and the taste and the smell of the tea are the most important parts of the ceremony, so the rules for making and pouring the tea are not always the same. In most of China tea is made in small clay teapots. The pot is rinsed with boiling water and then the tea leaves are added to the pot using chopsticks or a bamboo scoop. The tea leaves are rinsed in hot water in the pot and then hot water is added to the leaves to make the tea. The temperature of the water is all important. It needs to be hot but if it is too hot it can spoil the taste. The art of preparing and making tea is called Cha Dao.

In less than a minute, the server pours the tea into small narrow cups but he doesn’t pour one cup at a time. Instead the cups are arranged in a circle and the server pours the tea in all of them in one go. He fills the cups just over half way. The Chinese believe that the rest of the cup is filled with friendship and affection. The server then passes a cup to each guest and invites him or her to smell the tea first. You should thank him by tapping on the table three times with your finger. Next each guest pours their tea into a drinking cup and they are asked to smell the empty narrow cup. Finally they drink the tea. It is considered polite to empty the cup in three swallows. If you drink tea in a teahouse or restaurant is it called Yum Cha, yum is to drink and cha is tea.

Tea is probably Russia’s favourite drink after vodka! It is made and served in teapots or samovars – a Russian tea kettle, which are often decorated with images from folk lore or fairy tale. Some tea drinkers use three teapots that sit on top of one another. The middle pot usually holds strong black tea, the small pot on the top holds herbal or mint tea, and the large pot on the bottom holds hot water. The teas can be mixed with each other and diluted with hot water as each cup is poured. Everyone can mix the type of tea they like. Tea is drunk from cups but more often Russians use a podstakanniki – a special glass in a silver holder and the tea is usually drunk after meals rather than with a meal, but when tea is made using a samovar it is ready for use throughout the day. A samovar is shaped like an urn and there is a special place for a small teapot to sit on the top. Water is heated in the samovar and a strong dark tea is made using lots of tea leaves in the teapot on top. The strong tea is called zavarka. The tea is so strong that it has to be diluted with water from the samovar before it can be drunk. A drop of tea is mixed with hot water taken from the tap or spout on the front of the samovar. As the water is used you need to refill the samovar and every few hours you have to make a fresh pot of black tea. Some samovars are small and only hold about three litres of water but some can hold up to 30 litres. Samovars are usually made from metal and are commonplace in a Russian home or restaurant.

Tea is probably Russia’s favourite drink after vodka! It is made and served in teapots or samovars – a Russian tea kettle, which are often decorated with images from folk lore or fairy tale. Some tea drinkers use three teapots that sit on top of one another. The middle pot usually holds strong black tea, the small pot on the top holds herbal or mint tea, and the large pot on the bottom holds hot water. The teas can be mixed with each other and diluted with hot water as each cup is poured. Everyone can mix the type of tea they like. Tea is drunk from cups but more often Russians use a podstakanniki – a special glass in a silver holder and the tea is usually drunk after meals rather than with a meal, but when tea is made using a samovar it is ready for use throughout the day. A samovar is shaped like an urn and there is a special place for a small teapot to sit on the top. Water is heated in the samovar and a strong dark tea is made using lots of tea leaves in the teapot on top. The strong tea is called zavarka. The tea is so strong that it has to be diluted with water from the samovar before it can be drunk. A drop of tea is mixed with hot water taken from the tap or spout on the front of the samovar. As the water is used you need to refill the samovar and every few hours you have to make a fresh pot of black tea. Some samovars are small and only hold about three litres of water but some can hold up to 30 litres. Samovars are usually made from metal and are commonplace in a Russian home or restaurant.

Tea ceremonies in both North and South Korea are similar to those held in Japan and China but are more informal than the ceremonies in Japan. Korean Buddhists monks spend many hours meditating and use the tea ceremony to help them meditate. But Koreans in general, see tea ceremonies as spiritual occasions that are closely associated with their religion. ‘Tea,’ they say, ‘is a healthy, enjoyable and stimulating drink, full of good qualities. It reduces loneliness and calms your heart; it is a comfort in everyday life’.

There are tea rooms in most cities and even small towns in Korea where friends can gather and drink tea together. Many Koreans today still have tea ceremonies for important occasions including birthdays and anniversaries. From 1392-1910, tea ceremonies were performed regularly at palaces in Korea. The “Day Tea Rite” was a common daytime ceremony, but the “Special Tea Rite” was reserved for specific occasions, including royal weddings and visits from leaders of other countries. There was one tea ceremony, however, to which the king was not invited. This was the Queen Tea Ceremony. The only male guest was the crown prince, the eldest son of the Queen. The other guests were female friends, family and servants of the Queen.

I’m of the considered opinion,

I’m of the considered opinion,