China is well known as the birthplace of tea. For hundreds of years the country produced the only teas known to the western world. China currently has 1,431,300 hectares planted with tea, and although much of it is produced for the home market, China still accounts for over 18% of world exports.

China is well known as the birthplace of tea. For hundreds of years the country produced the only teas known to the western world. China currently has 1,431,300 hectares planted with tea, and although much of it is produced for the home market, China still accounts for over 18% of world exports.

As well as black teas, China produces five other principal teas for which the country is famous: Green, Oolong, White, Flavoured and Compressed teas. With some exceptions – such as Lapsang Souchong, Gunpowder and Keemun – most teas from China are rarely found in the general marketplace.

Perhaps the most famous china tea is Lapsang Souchong, the best of which is found in the hills in north Fujian. It is a unique large leaf tea distinguished by its smoky aroma and flavour. The tarry taste is acquired through drying over pine wood fires. Legend has it that the smoking process was discovered by accident. An army was camping in a tea factory that was full of drying leaves which had to be moved to accommodate the soldiers. When the soldiers left, the leaves needed to be dried quickly, so the workers lit open fires of pinewood to speed up the drying. The tea reached the market on time and a new flavour had been created.

But the real reason why these teas from Fujian province have a smoky flavour is that in the early 17th century when the Chinese tea producers began to export their teas to Europe and America, green teas did not travel well and consequently lost quality during the 15-18 month. The producers developed a method of rolling, oxidising and drying the tea so that it would hold its quality for longer. Once the teas had been oxidised, they were spread on bamboo baskets which were placed on racks in the drying room. This was built over ovens that allowed the heat to rise up through vents in the ceiling and into the drying room above. To fire the ovens, the tea manufacturers used the local pine wood from the forests that surrounded the factories, as they do to this day, and as the wood slowly burned, it gave off a certain amount of smoke that was absorbed by the drying tea and gave it a lightly smoked, sappy, pine-like quality..

But the real reason why these teas from Fujian province have a smoky flavour is that in the early 17th century when the Chinese tea producers began to export their teas to Europe and America, green teas did not travel well and consequently lost quality during the 15-18 month. The producers developed a method of rolling, oxidising and drying the tea so that it would hold its quality for longer. Once the teas had been oxidised, they were spread on bamboo baskets which were placed on racks in the drying room. This was built over ovens that allowed the heat to rise up through vents in the ceiling and into the drying room above. To fire the ovens, the tea manufacturers used the local pine wood from the forests that surrounded the factories, as they do to this day, and as the wood slowly burned, it gave off a certain amount of smoke that was absorbed by the drying tea and gave it a lightly smoked, sappy, pine-like quality..

The factories that made those lightly smoked black teas in Fujian province still manufacture lightly smoked Lapsangs in exactly the same way as they did 400 years ago. The teas are often called Bohea Lapsangs – the term Bohea being a derivation of ‘Wuyi’, the name of the famous mountain area where these teas are made. They also manufacture the much smokier Lapsang Souchongs that are popular today.

Keemun is a popular black tea from Anhui Province. This is a ‘gonfu’ tea – which signifies that it is made with dexterity and skill to produce the thin tight strips of leaf without breaking the leaves. The tight black leaves produce a rich brown tea, which has a lightly scented nutty flavour and delicate aroma.

Yunnan is a black tea from the province of the same name in the south west of China. It has a rich, earthy, malty flavour similar to Assam teas and is best drunk with milk. It makes an excellent breakfast tea. Other wonderful Chinese black teas are Keemun Mao Feng (splendidly known as Hair Point) and Szechwan Imperial.

Many green China teas are still made in the traditional way, by using methods that have been handed down from generation to generation. However, more and more teas are now made in mechanised factories. Green teas are totally unoxidised (compared to black teas which are fully oxidised) and so the first stage of the manufacturing process is to kill any enzymes that would otherwise cause oxidation to take place. To de-enzyme them, the freshly plucked leaves are either steamed (to make ‘sencha-type teas) or tumbled quickly in a wok or panning machine (to make pan-fired teas) and are then rolled by hand or machine. Some teas are twisted, some curved, some rolled into little pellets. To remove all but 2-3% of the remaining water, the tea is then dried in hot ovens or over charcoal stoves.

Many green China teas are still made in the traditional way, by using methods that have been handed down from generation to generation. However, more and more teas are now made in mechanised factories. Green teas are totally unoxidised (compared to black teas which are fully oxidised) and so the first stage of the manufacturing process is to kill any enzymes that would otherwise cause oxidation to take place. To de-enzyme them, the freshly plucked leaves are either steamed (to make ‘sencha-type teas) or tumbled quickly in a wok or panning machine (to make pan-fired teas) and are then rolled by hand or machine. Some teas are twisted, some curved, some rolled into little pellets. To remove all but 2-3% of the remaining water, the tea is then dried in hot ovens or over charcoal stoves.

Most Gunpowder tea is produced in Pingshui in Zheijian Province. After it has been pan-fired to de-enzyme it, the leaf is rolled into small pellets and then dried. The pellets look remarkably like lead shot or gunpowder, giving the tea its descriptive name. The pellets come in different sizes – the smaller the leaf plucked and rolled, the smaller the pellet – and grades range from tiny ‘pinhead’ gunpowder to larger ‘peahead’ gunpowder. Gunpowder tea has a soft honey or coppery liquor with a herby smooth light taste.

Chun Mee literally means ‘precious eyebrows’ and the shape of the leaves give the tea its name. The processing of ‘eyebrow’ teas demands great skill in order to hand roll and dry the leaves to the correct shape at the right temperature for the correct length of time. These long, fine jade leaves give a clear, pale yellow liquor with a smooth taste. Other Chinese green teas include Longjing (Dragon’s Well) from Zheijiang; Taiping Hon Kui (Monkey King) from Anhui; and Youngxi Huo Qing (Firegreen).

Oolong is traditionally found in China’s Fujian province and Taiwan. Oolongs are semi-oxidised teas that vary from greenish rolled oolongs (that give a light, floral drink, reminiscent of lily of the valley, narcissus, orchid or hyacinth) to dark brown leafed oolongs that produce a drink with deeper, earthier flavours and lingering hints of peach and apricot. There are two ways to make oolongs. To manufacture the darker leafed oolongs, the freshly plucked leaf is withered, then shaken or ‘rattled’ in bamboo baskets or in a bamboo tumbling machine to slightly bruise parts of the leaf, then oxidised for a short time so that the bruised parts of the leaf begin to oxidise. When 60-70% oxidation has been reached, the leaf is dried.

Oolong is traditionally found in China’s Fujian province and Taiwan. Oolongs are semi-oxidised teas that vary from greenish rolled oolongs (that give a light, floral drink, reminiscent of lily of the valley, narcissus, orchid or hyacinth) to dark brown leafed oolongs that produce a drink with deeper, earthier flavours and lingering hints of peach and apricot. There are two ways to make oolongs. To manufacture the darker leafed oolongs, the freshly plucked leaf is withered, then shaken or ‘rattled’ in bamboo baskets or in a bamboo tumbling machine to slightly bruise parts of the leaf, then oxidised for a short time so that the bruised parts of the leaf begin to oxidise. When 60-70% oxidation has been reached, the leaf is dried.

To manufacture the greener oolongs, the leaf is withered and then wrapped inside a large cloth and rolled in a special machine. The bag is then opened and the leaf is spread out briefly to oxidise lightly. The leaf is repeatedly wrapped, rolled and oxidised until approximately 30% oxidation has been achieved. The tea is then dried to remove all but 2-3% of the remaining water. The most famous of these greener, light, fragrant oolongs is Tie Kuan YIn which has a hyacinth or narcissus character. All oolongs are better drunk black – which is fine by me, it’s the way I drink my tea anyway!

Tie Kuan Yin, an oolong, is made in China’s Fuijan province and in Taiwan. The name means ‘Tea of the Iron Goddess of Mercy’ who is said to have appeared in a dream to a local tea farmer, telling him to look in a cave behind her temple. There he found a single tea shoot that he planted and cultivated. The bush he grew is said to have been the parent bush from which all future tea plants have been cultivated to make this highly fragrant tea. It is today one of the most sought after oolongs around the world. Other recommended China oolong teas are Fonghwang Tan-chung, Shui Hsien (Water Sprite), Oolong Sechung and Wuyi Liu Hsiang, Huan Jin Qui (Yellow Golden Flower), Da Hong Pao (Great Red Robe), Loui Gui (Meat Flower) and Wuyi Yan (Bohea Rock).

Also cultivated in China’s Fujian province and Taiwan, pouchong teas are more lightly oxidised than most oolong teas. The name means ‘the wrapped kind’ which refers to the fact that the tea was traditionally wrapped in paper after the manufacturing process when the tea was ready for sale. Long, stylish black leaves brew a very mild cup with an amber infusion, floral overtones and a very smooth, sweet taste.

White teas traditionally come from China’s Fujian province too and are made from leaf buds and leaves of the Da Bai (Big White) tea varietal by the simplest process of all teas. The manufacturing process includes no withering, no steaming, no rolling, no oxidising and no shaping – very young new leaf buds and baby leaves are simply gathered and dried, usually in the sun. The best known white teas are Pai Mu Tan (White Peony) which is made using new leaf buds and a few very young leaves, and Yin Zhen (Silver Needles) which is made from just the new leaf buds.Pai Mu Tan Imperial is a rare white tea that is made from very small buds and a few baby leaves that are picked in the early spring, and once dried, look like lots of tiny white blossoms with a few darker leaves surrounding the white bud – from which it’s name arises, ‘White Peony’. Yin Zhen is also from Fuijan province. This tea is made from tender new buds that are covered in silvery white hairs and it’s name means ‘Silver Needles’.

White teas traditionally come from China’s Fujian province too and are made from leaf buds and leaves of the Da Bai (Big White) tea varietal by the simplest process of all teas. The manufacturing process includes no withering, no steaming, no rolling, no oxidising and no shaping – very young new leaf buds and baby leaves are simply gathered and dried, usually in the sun. The best known white teas are Pai Mu Tan (White Peony) which is made using new leaf buds and a few very young leaves, and Yin Zhen (Silver Needles) which is made from just the new leaf buds.Pai Mu Tan Imperial is a rare white tea that is made from very small buds and a few baby leaves that are picked in the early spring, and once dried, look like lots of tiny white blossoms with a few darker leaves surrounding the white bud – from which it’s name arises, ‘White Peony’. Yin Zhen is also from Fuijan province. This tea is made from tender new buds that are covered in silvery white hairs and it’s name means ‘Silver Needles’.

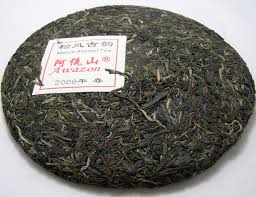

Puerh tea is named after Puerh city in Yunnan province, which was once the main trading centre for teas made in the area, so the official Chinese definition for Puerh tea is “Products fermented from green tea of big leaves picked within Yunnan province”. However, even Chinese specialists cannot agree on the true definition but, in general terms, Puerh teas are teas from Yunnan that are aged for up to 50 years in humidity- and temperature-controlled conditions to produce teas that have a typically earthy, yet smooth flavour and aroma. There are two types of Puerh tea made by two different methods of manufacture: Naturally Fermented Puerh tea (also known as Raw Tea or Sheng Tea) and Artificially Fermented Puerh tea (also known as Ripe Tea or Shou Tea).

To make Naturally Fermented Puerh tea, leaves picked from the bush are withered, de-enzymed in a wok, twisted and rolled by hand, dried in the sun, steamed to soften them and then either left loose or compressed into flat cakes or blocks. The tea is then stored in controlled conditions to age and acquire its typically earthy character. To make Artificially Fermented Puerh tea, the tea leaves are picked, withered, de-enzymed in a wok, twisted and rolled by hand, dried in the sun and then mixed with water, piled, covered with large ‘blankets’ made from hide and left to ferment. The tea is stirred at intervals and the whole process takes several weeks. When the teas have fermented to a suitable level, they are steamed and then left loose or compressed in the same way as Naturally Fermented Puerh teas. The teas are then stored in damp, cool conditions to age. Naturally Fermented Puerh teas are left for at least 15 for up to 50 years! Artificially Fermented Puerh teas are aged for only a few weeks or months. When ready, each cake of Puerh tea is wrapped in tissue paper or dried bamboo leaves. The reason for manufacturing Puerh teas by artificial fermentation is to allow the tea producers to make more Puerh in a shorter time. 50 years is a long time to wait for a good Puerh so the more modern artificial method was developed to meet a growing demand for these teas.

To make Naturally Fermented Puerh tea, leaves picked from the bush are withered, de-enzymed in a wok, twisted and rolled by hand, dried in the sun, steamed to soften them and then either left loose or compressed into flat cakes or blocks. The tea is then stored in controlled conditions to age and acquire its typically earthy character. To make Artificially Fermented Puerh tea, the tea leaves are picked, withered, de-enzymed in a wok, twisted and rolled by hand, dried in the sun and then mixed with water, piled, covered with large ‘blankets’ made from hide and left to ferment. The tea is stirred at intervals and the whole process takes several weeks. When the teas have fermented to a suitable level, they are steamed and then left loose or compressed in the same way as Naturally Fermented Puerh teas. The teas are then stored in damp, cool conditions to age. Naturally Fermented Puerh teas are left for at least 15 for up to 50 years! Artificially Fermented Puerh teas are aged for only a few weeks or months. When ready, each cake of Puerh tea is wrapped in tissue paper or dried bamboo leaves. The reason for manufacturing Puerh teas by artificial fermentation is to allow the tea producers to make more Puerh in a shorter time. 50 years is a long time to wait for a good Puerh so the more modern artificial method was developed to meet a growing demand for these teas.

Compressed tea include Tuancha, meaning ‘tea balls’ and are made in differing sizes, the smallest being half the size of a table tennis ball. These little balls are often made from Puerh aged tea and have an earthy flavour and aroma. Originally from Yunnan province, Tuocha, also a compressed tea, is usually a Puerh tea that has been compressed into a bird’s nest shape and has a similar earthy, elemental taste.

Lastly, there are the flavoured/scented teas, such as Jasmine, a china tea which has been dried with Jasmine blossoms placed between the layers of tea. The tea therefore has a light, delicate Jasmine aroma and flavour.Or how about Rose Congon, a large-leafed black tea scented with rose petals. The manufacture of ‘gongfu’ teas demand great skill in the handling of the leaves, the temperature control and the timing of each part of the process.The most famous of the flavoured or scented teas is of course, Earl Grey. Traditionally, this is a blend of black China teas treated with natural oils of the citrus Bergamot fruit which gives the tea it’s perfumed aroma and flavour. Earl Grey tea is said to have originally been blended for the second Earl Grey by a mandarin after Britain had completed a successful diplomatic mission to China. There are a number of other scented China teas that are popular, including Osmanthus, Magnolia, Orchid, Chloranthus and Lychee.

Lastly, there are the flavoured/scented teas, such as Jasmine, a china tea which has been dried with Jasmine blossoms placed between the layers of tea. The tea therefore has a light, delicate Jasmine aroma and flavour.Or how about Rose Congon, a large-leafed black tea scented with rose petals. The manufacture of ‘gongfu’ teas demand great skill in the handling of the leaves, the temperature control and the timing of each part of the process.The most famous of the flavoured or scented teas is of course, Earl Grey. Traditionally, this is a blend of black China teas treated with natural oils of the citrus Bergamot fruit which gives the tea it’s perfumed aroma and flavour. Earl Grey tea is said to have originally been blended for the second Earl Grey by a mandarin after Britain had completed a successful diplomatic mission to China. There are a number of other scented China teas that are popular, including Osmanthus, Magnolia, Orchid, Chloranthus and Lychee.

As you continue your journey through the tea of the world, I am learning to show a much deeper respect for my morning drink. Thanks for sharing this complex subject with us.

Glad you are enjoying it…